Welcome :)

4

Feb 26

Heads-up for Shairport-Sync

Building a Web Interface for Shairport-Sync

I’ve been running shairport-sync on various Raspberry Pis and other devices around my house for years. For those unfamiliar, shairport-sync transforms any Linux machine into an AirPlay audio receiver, letting you stream music from your iPhone, Mac, or any other Apple device to your stereo system, active speakers, or whatever audio setup you’ve cobbled together. And, I’ve definitely cobbled.

It works brilliantly, until you realise you have absolutely no idea what’s currently playing on any of your AirPlay receivers unless you’re standing in front of the device that’s streaming.

The Problem: Invisible Music

Here’s the scenario: You’ve got music playing somewhere in the house. Maybe it’s coming from the kitchen Pi, or perhaps the office setup. You want to skip to the next track, or see what album is playing, or just check who the artist is. Your options are:

- Walk to wherever your phone or iPad is

- Pick it up

- Hope it’s still on the right AirPlay output

- Check the now-playing info

The Solution: MQTT to the Rescue

Shairport-sync has a fantastic feature that many people don’t know about: it can publish metadata about what’s currently playing via MQTT. Album art, track info, artist details, even playback progress—it’s all there, ready to be enabled to stream over your local network in near real-time.

The problem? There wasn’t a simple, clean web interface to consume this information and provide basic transport controls.

So I built one.

Introducing shairport-mqtt-web

shairport-mqtt-web is a lightweight Flask web application that sits between your MQTT broker and your browser, giving you a clean, responsive interface to see what’s playing and control playback.

What It Does

The app provides:

- Real-time now-playing information: Artist, album, track title, and genre

- Album artwork display: Pulled directly from the stream

- Transport controls: Play/pause, next, previous, volume

- Playback progress: Track position with time remaining

- Server-Sent Events: Live updates without polling

How It Works

The architecture is straightforward:

- Shairport-sync publishes metadata to your MQTT broker

- The Flask app subscribes to these MQTT topics and maintains current state

- A web interface displays this information and sends control commands back via MQTT

- Server-Sent Events push updates to the browser in real-time

The state management is dead simple—just a Python dictionary holding the current playback information. When MQTT messages arrive, the state updates, and connected browsers get notified via SSE.

Why I Built It

As a self-described “maximizer” and maker, I get energized by designing and building solutions to real problems. Having music playable throughout the house is great, but not being able to see what’s playing at a glance felt like an itch that needed scratching. Not least becase someontimes I am not in the room and someone else wants to know what’s playing

More practically:

- I wanted something deployable: A systemd service that just works

- I wanted it lightweight: No heavy frameworks, no complex build processes

- I wanted it maintainable: Poetry for dependency management, clear structure

- I wanted it flexible: YAML configuration, easy to adapt to different setups

Technical Decisions

Why Flask?

Flask is boring technology, and that’s a compliment. It’s well-understood, has minimal overhead, and does exactly what I need without the ceremony of larger frameworks. For a simple web interface that primarily pushes state updates, it’s perfect.

Why Server-Sent Events?

WebSockets felt like overkill for one-way real-time updates. SSE is simpler, uses standard HTTP, and works brilliantly for pushing state changes from server to client. Plus, it’s just a text stream—easy to debug, easy to understand.

Why Poetry?

I’ve standardised on Poetry for all my Python projects. It handles dependency management, virtual environments, and packaging with minimal fuss. The Makefile wraps common operations making it trivial to run locally or deploy to production.

Deployment

The tool is designed to run as a systemd service on Linux systems. The deployment process is automated:

make deploy

This:

- Copies files to

/opt/shairport-mqtt-web - Creates a Python virtual environment

- Installs dependencies

- Sets up the systemd service

- Enables it to start on boot

It uses systemd’s DynamicUser feature, so no manual user creation is needed—the system handles security automatically.

What’s Next?

The tool does what I need it to do, which is the best kind of “done.” But there are a few nice-to-haves on my radar:

- Better mobile responsive design

- Support for multiple shairport-sync instances

- Playlist/queue visibility if shairport-sync exposes that data

- Historical playback tracking

- The random and repeat buttons don’t seem to do anything at this point – can’t quite work out if it is not supported or just not supported on my device. But I left them in just in case.

For now, though, it scratches the itch. I can pull up a browser tab (or pin it to my desktop), see what’s playing on any of my AirPlay receivers, and control playback without hunting for my phone.

Try It Yourself

If you’re running shairport-sync and have an MQTT broker handy, give it a spin:

git clone https://github.com/timhodson/shairport-mqtt-web.git

cd shairport-mqtt-web

make install

cp config.yaml.example config.yaml

# Edit config.yaml with your MQTT details

make prod

Then visit http://localhost:5001 and you should see your currently playing track (if something’s streaming).

The code is MIT licensed and available on GitHub. Contributions, issues, and feedback welcome.

Sometimes the best projects are the ones that solve your own specific problems. This one took a weekend to build and has been running reliably ever since. That’s the beauty of simple, focused tools built on boring technology.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I need to skip to the next track. Let me just open a browser tab…

28

Jan 26

Reverse Engineering a Bluetooth Badge

The Challenge

Cheap LED badges from AliExpress typically only work with proprietary mobile apps. I wanted full programmatic control—custom fonts, OSC integration, and command-line tools.

Why? well that’s a good question. I feel it could be useful to have a little matrix display that is controllable remotely – albeit near-remote as the range isn’t going to be huge. But could be fun to also see if it can be hardware hacked to have a permanent power feed. But that’s for the future.

Now I worked with Claude.AI to do this reverse engineering. I had started to do it on my own using traces and manually looking through for the packets and bytes that we were interested in – but I am not a native reader of binary and even less familiar with any typical encoding methods used for these things. So beyond using nRF Connect to inspect some characteristics, and establishing that I had caught the right things in the trace, I had managed to write some python code to find and connect to the device – and to see that connection happening on the badge.

But it wasn’t till I started exploring it with Claude Code that I started to ask the right questions – and one of the key thngs is that Claude had detected the possibility of AES encryption – something that I would never have thought of. That meant some more web research could find other things we could try.

So here is a summary of the process that Claude Code and I took to get to the result.

Phase 1: Traffic Capture

We started by capturing Bluetooth traffic between the official app and the badge using:

- Apple’s Bluetooth Debug Profile on iOS/macOS to capture HCI-level BTSnoop logs

- LightBlue for initial BLE service discovery

- Wireshark for packet inspection

This produced .btsnoop and .pklg trace files capturing real app interactions.

Phase 2: Binary Parsing

We wrote custom Python parsers (parse_btsnoop.py, parse_pklg.py) to extract ATT Write operations from the binary trace formats. This revealed encrypted 16-byte packets being sent to specific GATT characteristics.

Phase 3: Key Discovery

The packets were clearly AES encrypted. We initially tried the “Shining Masks” protocol key from similar badges—it didn’t work. Searching GitHub revealed the idealLED project with a different key: 34 52 2A 5B 7A 6E 49 2C 08 09 0A 9D 8D 2A 23 F8. This decrypted the traffic perfectly.

This feels like a bit of a lucky break really!

Phase 4: Command Protocol Analysis

With decryption working, we could see ASCII commands like LEDON, LEDOFF, MODE, SPEED, LIGHT, DATS, and DATCP. We documented the packet structure:

[length_byte][command_ascii][args][zero_padding to 16 bytes]Phase 5: Font Extraction

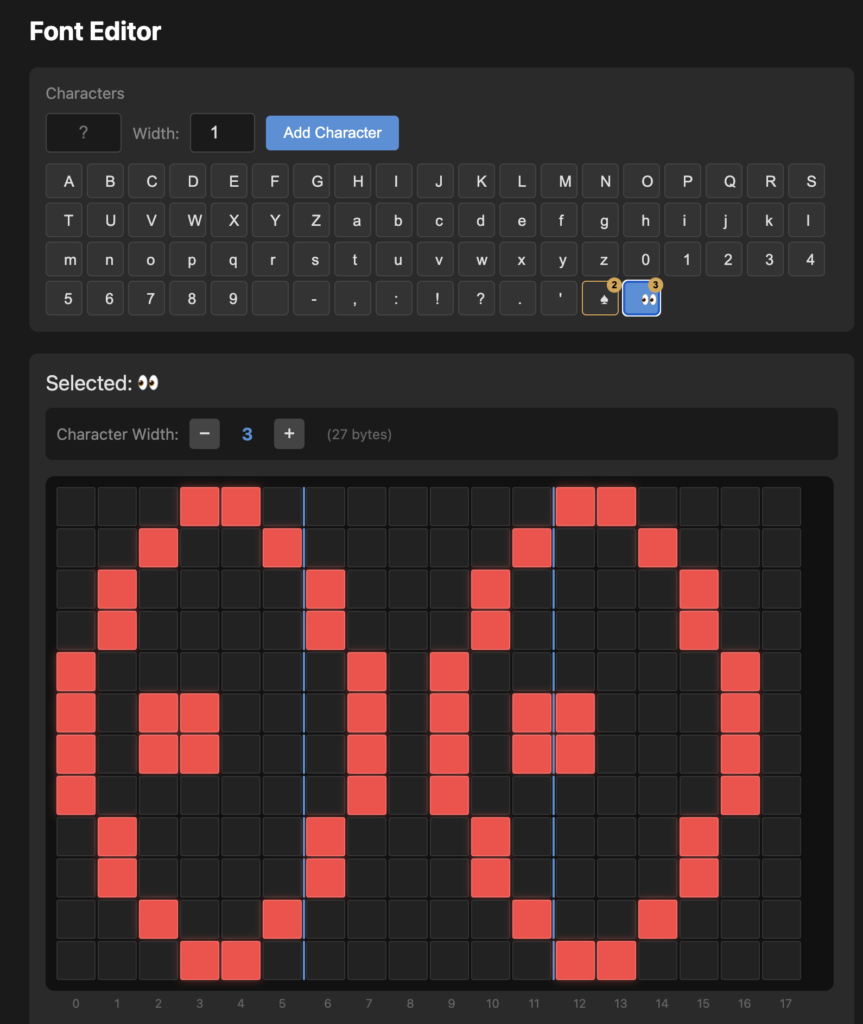

The trickiest part was understanding the 6×12 pixel character encoding. We captured a trace of the full alphabet (alphabet-trace.btsnoop), then wrote analyze_alphabet_trace.py to decrypt and visualise each character bitmap. This revealed an interleaved nibble layout across 9 bytes per character.

We sent various byte patterns to the badge to ‘show up’ where the bits were being written to.

Phase 6: Systematic Experimentation

The /experiments/ folder contains ~10 failed attempts—wrong headers, wrong characteristics, wrong data formats. Each failure narrowed the search space. Preserving these dead-ends proved invaluable for debugging.

The Result

A complete Python library with CLI, a web-based font editor, and an OSC server for creative tool integration—all without any manufacturer documentation.

The web based font editor can even connect to the badge directly (if chrome has it’s bluetooth connection capability enabled) so that characters can be tried out on the badge to see how it looks

I’ve pushed the code live and it can be found open source on github

https://github.com/timhodson/ble-led-badge

Key Takeaways

- Capture real traffic first—don’t guess at protocols

- Search for similar projects—someone may have already found the encryption key

- Keep failed experiments—they document what doesn’t work

- Visualize your data—plotting character bitmaps revealed encoding patterns that hex dumps obscured