Welcome :)

28

Jan 26

Reverse Engineering a Bluetooth Badge

The Challenge

Cheap LED badges from AliExpress typically only work with proprietary mobile apps. I wanted full programmatic control—custom fonts, OSC integration, and command-line tools.

Why? well that’s a good question. I feel it could be useful to have a little matrix display that is controllable remotely – albeit near-remote as the range isn’t going to be huge. But could be fun to also see if it can be hardware hacked to have a permanent power feed. But that’s for the future.

Now I worked with Claude.AI to do this reverse engineering. I had started to do it on my own using traces and manually looking through for the packets and bytes that we were interested in – but I am not a native reader of binary and even less familiar with any typical encoding methods used for these things. So beyond using nRF Connect to inspect some characteristics, and establishing that I had caught the right things in the trace, I had managed to write some python code to find and connect to the device – and to see that connection happening on the badge.

But it wasn’t till I started exploring it with Claude Code that I started to ask the right questions – and one of the key thngs is that Claude had detected the possibility of AES encryption – something that I would never have thought of. That meant some more web research could find other things we could try.

So here is a summary of the process that Claude Code and I took to get to the result.

Phase 1: Traffic Capture

We started by capturing Bluetooth traffic between the official app and the badge using:

- Apple’s Bluetooth Debug Profile on iOS/macOS to capture HCI-level BTSnoop logs

- LightBlue for initial BLE service discovery

- Wireshark for packet inspection

This produced .btsnoop and .pklg trace files capturing real app interactions.

Phase 2: Binary Parsing

We wrote custom Python parsers (parse_btsnoop.py, parse_pklg.py) to extract ATT Write operations from the binary trace formats. This revealed encrypted 16-byte packets being sent to specific GATT characteristics.

Phase 3: Key Discovery

The packets were clearly AES encrypted. We initially tried the “Shining Masks” protocol key from similar badges—it didn’t work. Searching GitHub revealed the idealLED project with a different key: 34 52 2A 5B 7A 6E 49 2C 08 09 0A 9D 8D 2A 23 F8. This decrypted the traffic perfectly.

This feels like a bit of a lucky break really!

Phase 4: Command Protocol Analysis

With decryption working, we could see ASCII commands like LEDON, LEDOFF, MODE, SPEED, LIGHT, DATS, and DATCP. We documented the packet structure:

[length_byte][command_ascii][args][zero_padding to 16 bytes]Phase 5: Font Extraction

The trickiest part was understanding the 6×12 pixel character encoding. We captured a trace of the full alphabet (alphabet-trace.btsnoop), then wrote analyze_alphabet_trace.py to decrypt and visualise each character bitmap. This revealed an interleaved nibble layout across 9 bytes per character.

We sent various byte patterns to the badge to ‘show up’ where the bits were being written to.

Phase 6: Systematic Experimentation

The /experiments/ folder contains ~10 failed attempts—wrong headers, wrong characteristics, wrong data formats. Each failure narrowed the search space. Preserving these dead-ends proved invaluable for debugging.

The Result

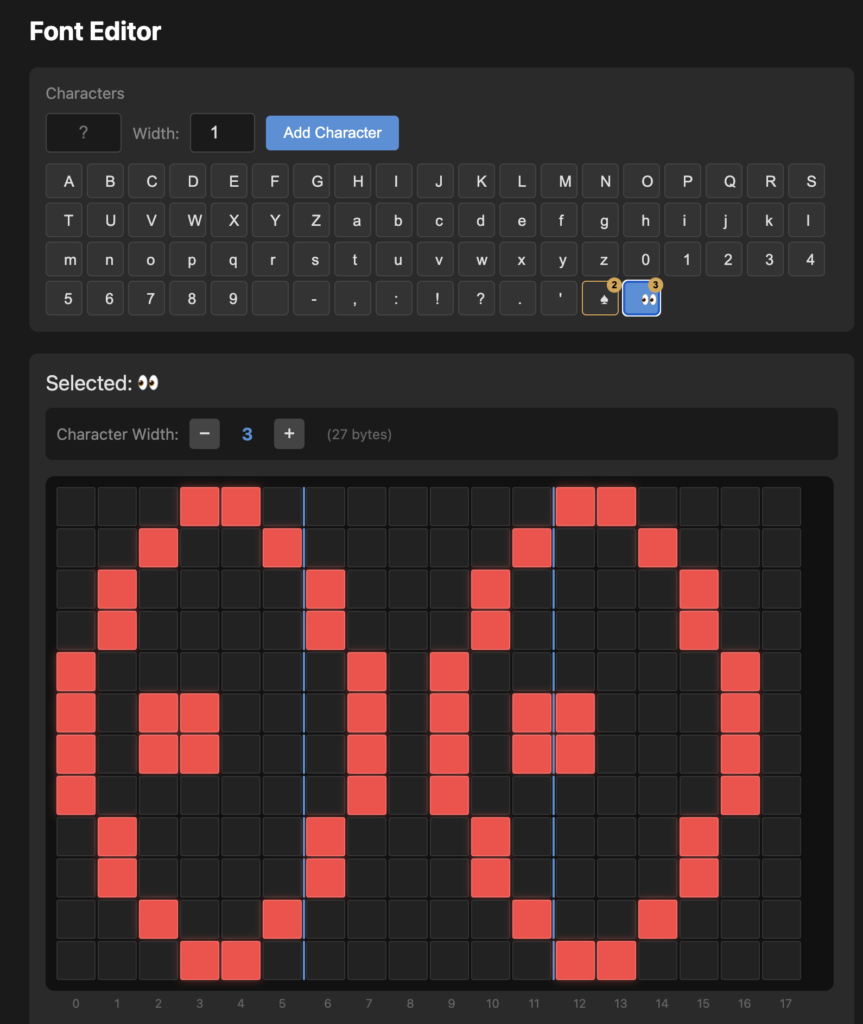

A complete Python library with CLI, a web-based font editor, and an OSC server for creative tool integration—all without any manufacturer documentation.

The web based font editor can even connect to the badge directly (if chrome has it’s bluetooth connection capability enabled) so that characters can be tried out on the badge to see how it looks

I’ve pushed the code live and it can be found open source on github

https://github.com/timhodson/ble-led-badge

Key Takeaways

- Capture real traffic first—don’t guess at protocols

- Search for similar projects—someone may have already found the encryption key

- Keep failed experiments—they document what doesn’t work

- Visualize your data—plotting character bitmaps revealed encoding patterns that hex dumps obscured

16

Dec 25

What We Built While Everything Was Being Taken Apart

News has emerged that, after divesting the Talis product suite to Kortext, Sage Publishing has let the Lean Library product suite go in a management buyout. It will be interesting to see what direction the Lean Library product suite takes from here. This means that Technology from Sage is no more.

You can read the press release and draw your own conclusions about how “deeply” Sage believed in lean library.

This marks the end of several months of upheaval and the beginning of more uncertainty as people are laid off right before Christmas. Many are angry and hurt by how the process was handled. My own observed experience showed that communication swung between poor and nonexistent, fuelled by a legalistically cautious “say nothing” mindset. I can only assume that this wasn’t unique to my situation. Maybe I’ll unpack some of the lessons in a future post. For now, it’s still too raw to be fully objective.

Instead, I want to highlight some of the things that we did as individuals who worked together collaboratively. Three different companies were put together to form Technology from Sage. They each brought a need to streamline process and communications. To understand each other. To understand the market they operated in.

None of the things we achieved happened without people on the ground using their knowledge, expertise, experience and enthusiasm to bring good ideas to the table. There were the inevitable frustrations when good ideas were not listened to, but despite the odds I think we achieved some remarkable things.

Speaking from my own perspective, the Operations Team were the interface between all the different teams and the customers. We (Laura Unwin and I) made it our business to find out what is happening. To ask the ‘why’ question as often as possible and many times when it wasn’t comfortable. We established clear communication lines with the Product Team, Technical Teams, Sales Teams, Marketing Team and Leadership Team.

We fought for visibility of process so that the endless check-in update style meetings could be dispensed with in favour of specific places that people could go and look to get the information they needed when they needed it and without having to wait for next week’s meeting.

We brought three different support systems together into one so that the whole team could see exactly what tickets were coming in and how they could be dealt with. We set it up so that everyone could own all tickets regardless of product, meaning that there was always someone who could see the new tickets coming in, or the old tickets that had sprung back into life, and take appropriate action.

We documented everything. Every process had decision trees written out so that they could be reviewed by those for whom it was new, or tweaked for those who saw an opportunity to make something more efficient. The goal was to understand why we did something and never do anything just because that was the way we had always done it. And we certainly never wanted to enter the same data in multiple systems in order to try and keep teams on track.

We championed transparency. We could see exactly which stories the developers were working on. We could see which product briefs the Product team were building out. We could comment on anything, supplying examples of customer behaviours to help a member of the Product Team get into the detail on a new feature, finding specific records that the development teams could use to build tests around, finding customers that the marketing teams could use as exemplars. We supported the teams around us by understanding what it is they needed, when they needed it, and how to get it to them.

We built our people up. We encouraged them into new skill areas. We spent time with them on difficult problems. We helped them to have a voice. We encouraged them to champion the customer and to ask difficult questions. We backed them up. We helped the business see our team as a source of truth.

Now we’ve watched that hard work unravel due to what felt like an abrupt shift in direction from the parent company, which only months earlier had described its commitment as a long-term one. We were apparently “the future”. Trust in the message and those delivering it evaporated when one day in September we sat in an all hands meeting being told how great the summer has been and championing the successes of the teams. The very next afternoon we were told that the end was less than a month away, and we now should plan to tear it all apart. A stark contrast. To split teams. To extract systems. To face an uncertain future.

It has been hard, and will still be so. But I am so very proud of the people we worked with on the ground. The people who came together during the worst of times with care and compassion for each other. The people who faced what felt like the bureaucratic impersonality of HR when dismissals came with no prior communication or indication that they were imminent. The people who stood by their principles. The people who were left behind with an uncertain future and who now look for other roles.

We bear the impact of decisions in which we had no say. That impact may take time to fully settle, but I hope that as we move into new roles and organisations, these experiences will shape our character. I hope we will carry forward the lessons we’ve learned, using our influence and position to act with greater empathy, clarity, and effectiveness than we were able to in the past.